- Home

- Peter Moreira

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler Read online

Published 2014 by Prometheus Books

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler: Henry Morgenthau Jr., FDR, and How We Won the War. Copyright © 2014 by Peter Moreira. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Prometheus Books recognizes the following registered trademarks and trademarks mentioned within the text: Bugs Bunny™, Donald Duck®, Gallup®, and Lockheed Martin®.

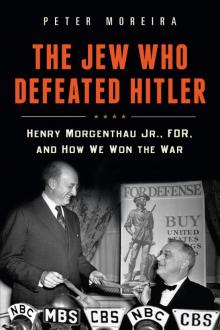

Cover image © Corbis

Jacket design by Nicole Sommer-Lecht

Inquiries should be addressed to

Prometheus Books

59 John Glenn Drive

Amherst, New York 14228

VOICE: 716–691–0133

FAX: 716–691–0137

WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM

18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Moreira, Peter.

The Jew who defeated Hitler: Henry Morgenthau Jr., FDR, and how we won the war / Peter Moreira.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61614-958-1 (hardback) — ISBN 978-1-61614-959-8 (ebook)

1. Morgenthau, Henry, 1891-1967. 2. Cabinet officers—United States—Biography. 3. United States. Office of the Treasurer—Biography. 4. Jews—United States—Biography. 5. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882-1945. 6. World War, 1939-1945—Finance. 7. World War, 1939-1945—Economic aspects. 8. United States—Economic policy—1933-1945. 9. United States—Politics and government—1933-1945. I. Title.

E748.M73M67 2014

352.2’93092—dc23

[B]

2014023881

Printed in the United States of America

When the final history of the Roosevelt Administration is written, it will be said that Henry Morgenthau, next to his chief, did more for the war than any other one man in Washington.

—Syndicated Columnist Drew Pearson

July 30, 1945

Prologue

1. Battling the Aggressors

2. The French Mission

3. The Gathering Storm

4. The Phony War

5. The Assistant President

6. Aiding Britain

7. Lend-Lease

8. The Sinews of War

9. The Jews

10. Bretton Woods

11. Octagon

12. The Morgenthau Plan

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

The scrapbook recording the Morgenthau family’s 1938 summer vacation in France lies in a cardboard archive box in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum in Hyde Park, NY. Its dark, Depression-era cover has weathered the years badly, and the newspaper clippings stuck to its rigid pages have yellowed. Yet it chronicles a seminal event in the family history. Henry and Elinor Morgenthau took their three children to Europe each summer, always in grand style due to the income they drew from their families, who were wealthy New York businesspeople. On this particular trip, the Morgenthaus and their Scottish maid, Janet Crawford, crossed the Atlantic in three first-class cabins aboard the Dutch ocean liner Statendam. What made this trip special was that the Morgenthau children were entering adulthood, Europe was simmering with tension, and Henry Morgenthau Jr. was being hailed for the first time as a statesman.

The Morgenthau children—Henry, who was twenty-one, Robert, nineteen, and Joan, sixteen—were now old enough to enjoy all that Europe offered, and the spirit of adventure was accentuated by the brewing of a nascent war. Their father was convinced their steward aboard the ship was a German spy because of his accent and manner. Later, the boys spent late nights reveling in Paris. Languishing on the rocky shores of the Côte d'Azur in southern France, the family mingled with the film star Marlene Dietrich, the author Erich Maria Remarque, and the vacationing family of Joseph P. Kennedy, the American ambassador in London. The paths of the two Democrat families would often cross in the ensuing years. Robert Morgenthau would one day organize John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign in the Bronx and would be with Robert Kennedy on November 22, 1963, when the call came in that the president had been shot in Dallas.1

The thing that really stands out in the scrapbook was the adulation Henry Morgenthau Jr. received in Paris. He had been secretary of the Treasury for almost five years, but this was the first time he was treated abroad as a man who influenced events. His greatest achievement had been the Tripartite Pact of September 1936, a treaty with France and Britain that aimed to reduce the harmful volatility among the three countries’ currencies. Morgenthau had been regarded as a lightweight until he sealed that pact—a feat few thought possible. More recently, he had been the main player in talks to stabilize the French franc, which was being battered by a faltering economy, a capital drain, and growing defense spending. And the French that summer made sure Morgenthau knew how much they appreciated his efforts.

The newspaper Excelsior ran a front-page photograph of the Morgenthaus being met at the Gare du Nord by US ambassador William Bullitt on July 24, and the coverage continued in all the major papers, even those outside France. The Daily Mail in London ran a photo of Elinor and Bullitt leaving the Élysée Palace after a meeting with President Albert Lebrun. Outside the French Treasury, on the bank of the Seine, Morgenthau was photographed by one paper surrounded by France’s leaders. In another, he was pictured addressing platoons of reporters. The Financial Times and other papers reported on the splendid banquet that Raymond Patenôtre, the minister of national economy, held for Morgenthau in the beautiful state dining room of the Quai D'Orsay. The press covered his meeting with Finance Minister Paul Marchandeau, the dinner with the prime minister and other cabinet ministers at the American embassy, and his luncheon with Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet.2

“That sort of social function isn't at all to my liking, but I couldn't help feeling proud at the high esteem in which the French hold Henry,” Elinor wrote to her parents. She was also proud of her children, who conducted themselves with such dignity at the formal dinners. “To see little Joan sitting next to the head of the Bank of France and talking with the air of a grown person was quite a sight,” she said.3 Certainly the whole family felt proud of Henry’s celebrity. “It is a grand change for you and, no doubt, you will realize what a following you have abroad,” wrote his father, the original Henry Morgenthau, from Murray Bay, Quebec, where he had listened to radio broadcasts relayed from a transmitter in Nova Scotia. “I hope you will enjoy it to the fullest.”4

Henry Morgenthau Jr. was indeed enjoying himself to the fullest. He was relaxed and jolly in his meetings with the French leaders and even with the journalists who followed him everywhere. He had received two substantial checks from the family funds before he left the United States, so he was flush with cash. And it had been three weeks since he had suffered from a migraine headache, a debilitating affliction that often drove him throughout his career to recline in darkened rooms. He was even more upbeat about the stability of France and her currency. “The French feel a little more optimistic and I think that their feeling is justified,” he wrote his father from Antibes. “Things have picked up here and their government is more stable.” At the end of the letter, he noted that there was one aspect of the vacation that was troubling him: “I get a great many letters for appeal from refugees but I can not do anything to help the poor th

ings.”5

After they finished relaxing on the Côte d'Azur, the Morgenthaus traveled up the eastern border of France and into Switzerland for the final leg of their journey. They ended up in Basel, the country’s third-largest city, located on the banks of the Rhine at the juncture of the Swiss, French, and German borders. From this ancient commercial hub, the Morgenthaus could gaze across the river and see Germany. One day, Henry III told his father he wanted to walk across the bridge and go into the country. His father was shocked by the statement and asked why. The young man simply said he wanted to be able to say he'd set foot in Germany.

“Oh, Henry,” said his father. “You don't want to set foot in Germany.”6

Even without the letters he'd received from oppressed German Jews, Henry Morgenthau Jr. was well aware of the hell that was unfolding across the river. Germany was now in its sixth year of Nazi rule, and Führer Adolf Hitler was rearming, expanding, and oppressing his enemies. Since seizing power in early 1933, he had renounced the Treaty of Paris, which prohibited German rearmament and demanded reparations. Then he'd brought in the Nuremburg Laws of 1935, depriving Jews of German citizenship and outlawing marriage between Jews and other Germans. He had taken over the Rhineland in March 1936 and annexed Austria in March 1938. And now, in the summer of 1938, he was insisting Germany be given the Sudetenland, the industrial portion of Czechoslovakia with a substantial German population. A man of Morgenthau’s acumen, especially a Jewish man, could not ignore the Nazi menace germinating nearby.

The lurking Nazi menace even appears in the family’s vacation album. Tucked in the back of the scrapbook is a small article from an unnamed French paper, noting that Morgenthau’s visit to Europe had drawn the attention of Hitler’s chief propagandist, Joseph Goebbels. The article, dated August 25, 1938, reported that Der Angriff, Goebbels’s official publication, had launched a violent front-page attack on Morgenthau. The article called him “the real chief of a wide Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy” against Germany and her friends and said the secretary was engaged in “mysterious intrigues” during his trip to France. “Mr. Morgenthau did not come to Europe for a rest, as he pretends, but [was] charged with a special mission by Mr. Roosevelt,” said Der Angriff. “Moreover, it is he who, behind the president, holds the power.”7

Of course, Der Angriff had frequently attacked the Jews who surrounded President Roosevelt for years and would continue to do so until 1945. But until 1944, it rarely singled out Morgenthau. The Nazi media frequently mentioned that Roosevelt had surrounded himself with Jews, but it usually referred to them as a group. Besides Morgenthau, the circle included financier Bernard Baruch, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, speechwriter Sam Rosenman, Congressman Sol Bloom, and even New York mayor Fiorello Henry La Guardia, whose mother had Hungarian Jewish lineage. If the Nazis gave one Jew prominence, it was Baruch, who had led the War Industries Board in World War I. And the right-winged media on the Continent could take the issue of “International Jewry” to comical heights. In October 1938, the Fascist journalist Giovani Preziosi wrote in the magazine La Vita Italiana that the Jewish International was planning to take power in the 1940 US election. Baruch would be president, he wrote, and the cabinet would include Albert Einstein as vice president, Herbert Lehman as secretary of state, Henry Morgenthau Jr. as Treasury secretary and Leon Trotsky as secretary of war. Walter Lippmann would be secretary of the press.8

Americans also noticed the unprecedented preponderance of Jews surrounding the president. Several wags, such as poet Ezra Pound and farm leader Milo Reno, referred to the New Deal, Roosevelt’s recovery program, as the “Jew Deal.”9 Some called the government “the Rosenbaum Administration.” But what is difficult to understand for people born generations later is that the Nazis actually believed their own propaganda. The men surrounding Hitler were sick sadists whose ravings about an international Jewish conspiracy seemed ludicrous to reasonable people. But the Nazis themselves actually believed there was an international Jewish conspiracy, and a substantial body of the European population agreed with them. In one of history’s cruel coincidences, Jews gained unprecedented political power in the United States just as the Nazis were coming to power in Germany. When Roosevelt aligned himself with the British and later entered the war, it served only to vindicate the Nazis’ conviction that an international network of Jews was at work against their country.

Of all the American Jews frequently cited by the Nazis as being part of this conspiracy, only Morgenthau held an executive position and wielded the power necessary to fight the Axis. The thesis of this book, as the title suggests, is that Morgenthau’s role in the war was utterly crucial to the Allied victory to a degree that history has not appreciated. He was certainly the most powerful Jew in the world while Jewry faced its greatest peril since the days of Moses.

I admit the title The Jew Who Defeated Hitler somewhat overstates the case. No single person—not Stalin, nor Churchill, nor Roosevelt, nor any soldier—defeated Hitler. The single biggest reason that the Nazis fell was the Soviet acceptance of suffering and casualties in order to withstand the German onslaught. More than twenty million Soviets died in the war, three times the number of Germans. I'd argue that the second-biggest reason for the Allied victory was that the industrial might of the Allies tripled that of the Axis. “The Allies possessed twice the manufacturing strength (using the distorted 1938 figures, which downplay the US share), three times the ‘war potential’ and three times the national income of the Axis powers, even when the French shares are added to Germany’s total,” writes Paul Kennedy in The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers.10 (War potential is the segment of the economy that can be used for waging war.) The Allies were certain to win, regardless of the excellence of the German military leadership, simply because they had three times the economic clout and could devote a larger portion of their economy to manufacturing arms and financing their forces.

And who was the main administrator harnessing the economic might of the strongest member of the alliance? Henry Morgenthau Jr.

Historians have tended to downplay his role because he is viewed as a yes-man to Roosevelt, so Roosevelt has gotten the credit for Morgenthau’s work because academics assumed he was simply doing the president’s bidding. What’s more, Morgenthau was never an easy historical study. Oh, he wanted to be remembered by history. He even wanted to handpick the historian to write his biography. He went to pains to set up a recording system in his office—similar to that of Richard Nixon—and had a pool of secretaries to transcribe all meetings and phone calls. He frequently had stenographers come to his house if he met people there in the evenings. He filed away every document that crossed his desk, an archive that eventually became known as the Morgenthau Diaries. These official documents and his personal papers totaled one million pages. As early as May 1941, Morgenthau hired a Treasury underling named Joseph Gaer to assemble material for a planned biography. He agreed to pay Gaer $6,500 per year from his own pocket for the work, which fell by the wayside as war broke out.11 After the war, he called in Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. to help him write memoirs for Collier's magazine. In 1954, Morgenthau asked the Yale historian John Morton Blum to write the story of his years with Franklin Roosevelt. The ensuing project consumed twelve years of Blum’s life and resulted in a three-volume work titled From the Morgenthau Diaries. The greatest omission in these works is the role of Elinor Morgenthau. Henry Morgenthau Jr. made certain his wife’s remarks were rarely recorded, likely to protect her privacy, and refused to discuss Elinor with Blum during their long collaboration. Morgenthau’s own legacy suffers because of this. Elinor Morgenthau was brilliant—her mind was analytical, her opinions cogent and precisely expressed. Yet little of Elinor’s advice has been recorded. The Morgenthau story would be all the richer if we had a stronger appreciation of her influence.

Morgenthau proves a challenge as a historical hero. He was not made of heroic stuff. In a time of great military feats, he was a bureaucrat, and his greatest strength was his

ability to make governments act. He was thin skinned and would often snitch to the president about his cabinet colleagues. He was inarticulate—so much so that it is all but impossible to convert his discourse into readable quotations. His diction was a tangle of incomplete sentences, malapropisms, and meandering dependent clauses, all overlaying his own brand of Runyonesque New York street talk. He was also the ultimate multitasker, frequently engaged in five or six different sets of simultaneous negotiations, lasting for months or years, involving several countries. He oversaw the most unwieldy of government departments, and because of this, historians have a hellish task in stringing together a storyline in the Morgenthau biography. There are simply too many threads. He set the budget, negotiated exchange rates, issued bonds, oversaw the coast guard and the Secret Service, and maintained public buildings. He even had more responsibility for monetary policy than his modern successors. And those were simply the responsibilities within his portfolio. He frequently took on other jobs because he didn't think other secretaries were doing their job properly. Quite often, Roosevelt agreed with him. (And on a few occasions, the president brought in other people to do the work of the Treasury because he didn't like what Morgenthau was doing.)

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler will sidestep this chaotic administrative workload by focusing on Morgenthau’s efforts to help defeat Germany, Japan, and Italy. It is the story of the American who raised more than $300 billion in debt and taxes to battle the greatest combination of power and evil the world has ever seen. As perspective, consider that the Roosevelt government spent $33.5 billion in the five years of the New Deal, the Roosevelt administration’s program to overcome the Great Depression. It was a program criticized for creating so much public spending that it might bankrupt the country.12 The war against the Axis was the most expensive human undertaking ever, and the man most responsible for financing it was Henry Morgenthau Jr. It is true Morgenthau did little without FDR’s approval, but this book will show that Morgenthau urged Roosevelt to prepare for war while the president was still waffling. He was the early architect of the US airplane program, he was instrumental in rearming Britain after Dunkirk, and he exceeded expectations in raising hundreds of billions of dollars at low interest rates. And he was the driving force behind the War Refugee Board, which helped to rescue about 200,000 European Jews. He did all this even though he had little formal education, was considered stupid, had to battle enemies within the administration and Congress, and faced anti-Semitism. This is the story of how Morgenthau led the Treasury to finance the dismantling of the Nazi juggernaut and how his final gambit led to his inglorious political downfall.

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler