- Home

- Peter Moreira

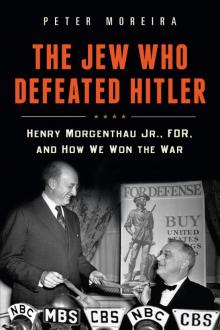

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler Page 12

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler Read online

Page 12

Roosevelt knew he had to settle the situation, likely by firing Woodring. But he hated to fire a faithful lieutenant, and Woodring could deliver the Kansas delegates at the convention, should FDR run for the presidency again in 1940. So with Europe embroiled in an expanding war, the War Department was dysfunctional and the government had no sound procurement structure to oversee the pending arms buildup. Roosevelt therefore established a liaison committee on December 6, 1939, to work with English representative Arthur Purvis and his French counterpart René Pleven in securing matériel for the hard-pressed democracies in Europe. The committee’s chairman was the acting director of procurement in the Treasury, Capt. Harry Collins. Morgenthau did not at first have an official position on the committee, but in fact he provided the muscle often needed to get through the bureaucracy to ensure French and British orders were filled. The committee’s power lay in Morgenthau’s ability to bring concerns directly to Roosevelt and bypass both Woodring and Johnson.3 Woodring objected to the committee, arguing to Roosevelt that the Army and Navy Munitions Board was handling the matter competently and there was no need to bring in the Treasury. He wanted the War Department, not the Treasury, to decide what the allies would receive, and Johnson agreed with him. Roosevelt sided with the Treasury. “I think you fail to realize that the greater part of such purchases is not, in the strict sense of the word, munitions—probably well over 50 per cent of the purchases will consist of articles of raw and semi-raw materials which are primarily of civil use,” the president wrote Woodring.4

Ignoring the War Department’s complaints, Morgenthau went to work with Purvis, who he grew to like immensely. First, they agreed the Treasury would help the British with such matters as helping to prevent arms manufacturers from raising prices for foreign buyers. The Vinson-Trammel Act of 1934, designed to encourage naval construction, restricted the profit on arms contracts for the War Department, but the rules were vague for foreign orders. Morgenthau had his staff vet the terms for the British orders.5

While he prevented profiteering by arms producers, Morgenthau knew he needed private industry to meet the requirements of the war, and he hoped to work with industry to iron out the sundry small problems that were delaying projects. As early as September, for example, Morgenthau learned the navy was a year behind on the construction of six battleships simply because a manufacturer was unwilling to invest the $6 million needed to make armor plate, largely because of complications over depreciation on equipment.6 One key shortage was smokeless powder, a modern propellant used in firearms and artillery. The US Army had too little of this compound, and the entire country had the capacity to produce only 6,500 tons annually. Purvis concluded that the British alone needed 32,400 tons each year, not to mention 12,000 tons of TNT. To meet the immediate need, Morgenthau, with Roosevelt’s support, pressured the army to give powder and TNT to the British. The army complied, but only after the navy agreed to lend the land-based service some of its supply. Purvis and Pleven proposed spending about $20 million to build new US capacity on the condition that US manufacturers lend their skill and designs to simultaneous construction in Canada with an annual capacity of 12,000 tons. Louis Johnson came out strongly against the proposal, saying the United States had to focus on meeting its own obligations before contributing to plants in Canada. “Once the Allied Purchasing Mission has given firm contracts to increase production in this country over and above what it is now by twenty thousand tons…we would be very glad to give the Canadian government whatever assistance they need,” Morgenthau told Purvis. The British agent was forced to agree to the plan.7

One day in late January 1940, Morgenthau and Roosevelt sat down to sandwiches in the Oval Office and were enjoying a pleasant chat when Roosevelt offhandedly said, “I definitely know what I want to do.” Morgenthau knew he was referring to an unprecedented third term as president. Rather than state what decision he had reached, Roosevelt babbled on about possible convention sites, such as New York, Philadelphia, or Chicago. Finally, Morgenthau refocused the conversation, saying: “Just what did you mean when you said that you definitely knew what you wanted to do?”

Again Roosevelt did not give a straight answer but told the story of one consultant to the administration who delivered to the president a message from his wife: “Keep on just as you are but keep your mouth shut.” Morgenthau interpreted that as a strong hint he planned to run again.

“You know, Mr. President, you can count on me always,” said Morgenthau.

“I know that.”

“When I have lunch with you I want you to be comfortable and, therefore, I do not keep bringing up the third term issue.”

“Well Henry,” said the president, “it has gotten so far that it is a game with me. They ask me a lot of questions, and I really enjoy trying to avoid them.” He paused and then added, “I do not want to run unless between now and the convention things get very, very much worse in Europe.”8

Roosevelt frequently mentioned to Morgenthau that he was worried about the developments across the Atlantic, though Finland was the only active theater as the moment. The only action the Allies were experiencing was the Nazis’ relentless U-boat campaign, which was wreaking havoc on shipping. The Brits were starting to call it the “Phony War,” but Roosevelt felt sure the situation would deteriorate quickly and severely. Even in Asia, there was little actual battle as the Japanese consolidated their holdings on the coast and Chiang Kai-shek struggled to operate out of his landlocked base in Chungking. The Burma Road was still proving an inefficient means of transportation for the strapped government. The Chinese now wanted a $75 million, ten-year loan backed by 100,000 tons of tin. Jesse Jones, the head of the Export-Import Bank, which would have to issue the loan, was unwilling to lend more than $20 million, and Morgenthau began to negotiate yet again with the Chinese representatives.9

Having lost Herman Oliphant and John Hanes within a year, Morgenthau moved to strengthen his office. Daniel W. Bell, the budget director, was promoted to under secretary of the Treasury, the sixth in Roosevelt’s tenure. Bell lacked Hanes’s ties to business and wasn't as brilliant as Oliphant or Harry Dexter White, but he was dependable, hardworking, moderate, and loyal, and he knew government finance thoroughly. “I've been around here about six years and I've seen you teach a lot of under-secretaries, and it’s about time you reaped the harvest of twenty-eight years of faithful service,” said Morgenthau.10 He also brought in an innocuous businessman named John L. Sullivan from Manchester, New Hampshire, whose links to his home state were especially valuable in an election year. Though Morgenthau was known for not hiring flunkies from the Democratic Party, he wasn't above using his staff for party work. A week after announcing his appointment, Morgenthau sat Sullivan down in private conversation and told him the president wanted him to do some organization work in New Hampshire, the first state to choose delegates to the coming convention.11

Morgenthau pressed on with his primary duty of financing the government and the war effort. On January 3, the president delivered his annual budget message to Congress, which proposed a 7.4 percent decrease in expenditures for the year ending June 30, 1941, of $8.4 billion, including $1.8 billion in defense expenditures. “This is an increase, of course, over the current year, but it is far less than many experts on national defense think should be spent, though it is in my judgment a sufficient amount for the coming year,” said the president.12 By this time, Roosevelt had backed off his plan to raid the stabilization fund. The budget message began the negotiations with the two houses of Congress, the outcome of which would determine the final budget. Roosevelt told Morgenthau five days later he was happy with the response it drew and realized he still had a lot of horse trading to carry out with Congress before he got the budget he really wanted. “We sure have them fooled!” he told Morgenthau.13

By mid-January, the British, French, and US militaries were all increasing their armament orders, and Morgenthau was pressuring the president and the bureaucracy to do more to accele

rate deliveries. He wanted the president more involved to map out the army’s and navy’s needs for 1940 and 1941. The army in early January had a contract for 524 Curtiss-Wright P-40s, whose delivery would begin in March. The French had an order of one hundred of the same planes, but their deliveries were not to begin until July. The president on January 8 asked Morgenthau to ensure that twenty-five of the army’s planes be diverted to the French between April and June, and the army could take twenty-five of the French planes when its order began in July.14 “I did a magician’s trick for you,” Morgenthau told Pleven, “pulled 25 planes out of the hat.”15 Morgenthau demanded government officials make the airplane orders a priority. When Pa Watson, Roosevelt’s appointment manager, bumbled after being asked to schedule a meeting among the president, the liaison committee, and army and navy aviation representatives, Morgenthau lost his temper. “Well listen, I don't know what else he’s got but this is damn important,” he bellowed. “Do you know what this program involves? One point two billion dollars, and listen, fella, this is Allied money that is going to build up our airplane industry so that the Army and Navy will be on its biggest feet. I don't know of any cheaper way of doing it.”16

Not only did Morgenthau have to battle the military over the foreign orders, he was also trying to stop the State and Agriculture Departments from trying to convince the Allies to buy American agricultural products. He thought it a misuse of their precious capital. What’s more, his role of helping the Allies had never been announced publicly. By late January, Morgenthau had had enough and urged White House press secretary Steve Early to release a statement about his position working with the Allies. He complained that Louis Johnson “was dishing out…dirt about me, namely that I was more interested in the Allies than I was in my own country.” He added: “The whole War Department…has fought us to a standstill on this thing.” He deeply resented the assault on his patriotism because he was doing what the president had asked him to do.17

The White House announced on January 22 that Morgenthau would coordinate aircraft purchases for the military and the Allies, and the secretary explained at a press conference that the reason for the appointment was that the pressure for orders from France and Britain had become so great. “And don't let anyone tell you I don't look after our own interest first,” he told the reporters. The article in the New York Times explained that Morgenthau was charged with solving the problem of how to expand aircraft production without letting the foreign orders interfere with those of the US military.18

The job of airplane procurement became easier when the British in February said they would begin to sell off their US securities. By the end of April, the British raised a total of $310 million through two tranches of securities sales, and the markets were stable throughout. The only downside for Morgenthau was J. P. Morgan handled the sale.19 “Recent developments have served to emphasize the importance of Secretary Morgenthau’s position in relation to the expansion of aircraft output to meet the heavy orders on hand from the British and French,” said an article in the Wall Street Journal, which noted the secretary’s role in overcoming shortages in certain machine tools.20 He identified the shortage of machine tools—that is, the devices needed to shape the metal into parts for engines—as one of the key problems in expanding aircraft production. For example, Pratt and Whitney had ordered 700 different machine tools needed for existing orders but had received only 150 of them. Morgenthau met on January 30 with representatives of the National Machine Tool Builders’ Association to work out a means for overcoming these problems—the first time an intermediary between the airplane and the machine-tool industry had attempted to find solutions. One difficulty, he discovered, was that the machine-tool makers were overwhelmed with orders from the United Kingdom, France, Japan, and Russia. He convinced them to cancel or postpone the Japanese and Russian orders so the domestic and Allied contracts could be met.21

In early February, Morgenthau toured the plants of Pratt and Whitney in Hartford, Connecticut, and Wright Aeronautic Corporation, at Paterson, New Jersey, and afterward he hailed their growth of the airplane industry as the largest industrial expansion that had taken place in the United States in several years. The two plants he visited had expanded output by 50 percent even though they had received only about one-quarter of the machine tools they had ordered. And the expansion had been paid for entirely by the foreign orders.22 The Allies were now gearing up for a big order; Morgenthau was able to report to Roosevelt in mid-February that he believed existing orders could be met. Yet the success of the program did nothing to end the interdepartmental sniping.

After Roosevelt returned from a holiday sailing aboard the USS Tuscaloosa, a six-year-old, 9,975-ton New Orleans–class heavy cruiser, Morgenthau was able to tell the president on March 3 that the economy seemed to be picking up. Freight rates were rising, and the Allies had just told airplane manufacturers to prepare for a big order. He also asked to be allowed to raise money as soon as the economic and military situation was expected to sour in the spring. Then the secretary added that Johnson was still “all the time trying to undermine me through the press”23 and that Hull and Wallace were urging the Allies to buy pork products even though the priority should have been on arms purchases. Roosevelt was jocular through the meeting, but beyond question Morgenthau was beginning to feel like he was the only senior official in Washington helping democratic allies check the advance of the dictatorships.

The British and French together wanted to buy at least five thousand air frames and ten thousand engines and were willing to buy twice the number of each. Only a year and a half earlier, the United States had the annual capacity to produce only seven thousand aircraft, and Roosevelt’s talk of producing fifteen thousand planes a year seemed like a fantasy. Now capacity had increased to more than twenty-one thousand.24 Employment at aircraft and engine manufacturers had doubled to seventy-five thousand in the twelve months to April and was expected to reach 100,000 that summer.25 The United States was now able to exceed Germany in producing the key component in modern warfare.

Morgenthau and Bell arrived at the White House on March 4 for a perfunctory meeting with the president and White House economic adviser Lauchlin Currie on the Treasury’s regular financings. When they walked into the waiting room, they found Marriner Eccles ready to join them. Currie, a dyed-in-the-wool New Dealer originally from Nova Scotia, had obviously wanted liberal reinforcement while dealing with the Treasury secretary, so he had called in the chairman of the Federal Reserve. After a brief discussion, Bell and Morgenthau ascertained the other two had been talking about using the gold in the stabilization fund to redeem some maturing securities. Morgenthau reminded them again the stabilization fund money could not be used without the approval of Congress, and both Eccles and Currie agreed.

But once they were with Roosevelt, both Currie and Eccles argued the Treasury should hold off on refinancing until it knew what the new tax receipts would be. They also argued in various ways that the stabilization-fund gold could be used rather than going to the debt markets—if not now, then later. When Morgenthau asked Roosevelt whether he favored financing now or later, the president said he didn't want to become entangled in the details. He asked them to discuss the matter among themselves in the cabinet room.

Morgenthau later said Eccles “made one of his long-winded speeches,” admitting the matter was the sole responsibility of the Treasury but feeling duty-bound to share his opinion with the president. Currie said he didn't feel he should apologize to anyone for airing his views. Morgenthau said he got the impression his two opponents simply felt they had to use this gold for something to stimulate the economy. What they didn't know was White had lobbied Morgenthau for forty-five minutes that morning to take the same action with the stabilization-fund gold. Morgenthau was worn down. He was sick of people interfering with the facet of his job at which he excelled.26

“I take this very personally,” he later told a few staff members. “I was asking the President t

o decide. He was putting me in a position that I had to ask him to decide whether he was going to follow the Eccles-Currie school of thought or whether he was going to follow my advice.”27

In front of Eccles and Currie, he dictated a quick note to the president saying that Eccles preferred using the stabilization-fund gold in the near future, even if that meant refinancing only some of the maturing securities. The note spelled out that Morgenthau wanted to refinance all of them immediately. “I cannot take the responsibility of having such a large amount of government securities hanging over the Treasury at this time,” he concluded, asking for FDR to okay his funding plan before 4:00 p.m., when the president had a press conference. He read the note twice to Eccles to make sure that the central banker agreed with the summation of his views.28

“Well, that’s the same as resigning if you don't get it,” said Currie, referring to the conclusion.

“I don't threaten to resign,” said Morgenthau, overlooking the fact that he'd done so at least once in the past two years.

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler