- Home

- Peter Moreira

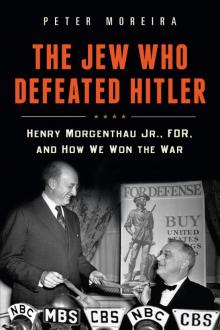

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler Page 29

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler Read online

Page 29

On the currency issue, the Treasury favored a weak occupation mark, a rate of twenty marks to the dollar, so US soldiers would have a lot of buying power. However, the British favored a stronger mark at an exchange rate of about five, while the State Department backed an exchange rate of eight. The stronger rate would protect British industry once the countries began to trade again. Roosevelt, Morgenthau knew, wanted the exchange rate left open so every soldier could negotiate when buying goods in Germany.

On the morning of August 25, Morgenthau called on the president, whom he saw less frequently than before. He knew Roosevelt was aging with disturbing speed. Just the night before at a dinner for the president of Iceland, FDR toasted the visiting dignitary, then waited while the guest responded with his own toast. Then Roosevelt toasted his guest again, having completely forgotten he had already done so. On this particular morning, the president’s appearance shocked Morgenthau. “I really was shocked for the first time because he is a very sick man and seems to have wasted away,” he dictated to his diary hours later.30

Morgenthau bore a memorandum pushing for a twenty-mark exchange rate, which FDR again turned down in favor of having no official rate. And Morgenthau voiced his concerns about another official document that signaled magnanimity toward Germany. The Handbook of Military Government had been prepared by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force as a guide for British and American forces overseeing the coming occupation government in Germany. The handbook instructed the military to install an efficient government as quickly as possible, to organize a working police force to maintain order, and to convert industrial plants to the manufacture of consumer goods. Regulations affecting industrial production and the methods of extracting raw materials from the earth should be maintained, unless specifically ordered otherwise. “The highly centralized German administrative system is to be retained unless otherwise directed by higher authorities,” said the handbook, which Morgenthau denounced strongly.31

After a rambling conversation on Germany and other matters, Morgenthau blurted out, “Mr. President, some time when you have time I would like to talk to you about myself because, looking forward to the next four years, I am kind of getting bored over at the Treasury, and I don't think you are making use of all my talents.” The president responded with the old bromide about the two of them one day retiring to Dutchess County and added they may find a role in the United Nations. Morgenthau persisted in discussing his own role in the administration, stressing that, like FDR, he believed the postwar foreign policy must focus on collaboration with Moscow. “I was able to work with Russia at Bretton Woods, and Dean Acheson said I seemed to have a sixth sense on those things,” he told the president.32

It seems obvious Morgenthau was lobbying to become the next secretary of state. He was the longest-serving Treasury secretary since the Madison administration, and the only promotion available was the State Department. (As a Jew, he could not realistically seek the presidency.) He had scored unlikely foreign-policy victories in the Tripartite Pact and Bretton Woods Accord. And there were few other candidates. Sumner Welles had resigned; Harry Hopkins was sick; Hull was exhausted; seventy-six-year-old Stimson was a Republican with ties to Wall Street. Morgenthau alone was robust, experienced, and ambitious. Even his migraine headaches had been held in abeyance recently, and through the end of August he had not missed a single day of work that year.33

“This so-called ‘Handbook’ is pretty bad,” Roosevelt wrote to Stimson the next day, siding with Morgenthau. “I should like to know how it came to be written and who approved it down the line. If it has not been sent out as approved, all copies should be withdrawn until you get a chance to go over it.” He wanted the German population to understand they were a defeated nation. They could be fed by US Army soup kitchens, he said, to keep the people healthy. “There exists a school of thought both in London and here which would, in effect, do for Germany what this Government did for its own citizens in 1933 when they were flat on their backs,” said the memo. “I see no reason for starting a WPA, PWA or a CCC for Germany when we go in with our Army of Occupation.”34 At a cabinet meeting that day, FDR struck a committee of Hull, Morgenthau, and Stimson and chaired by Hopkins (all of whom were given a copy of the handbook memo) to review the question of the treatment of Germany. Hull was characteristically bitter that the others were encroaching on his turf. As they departed for the Labor Day weekend, it was already becoming apparent that the main combatants would be Morgenthau and Stimson.

Trying to relax in Saranac, New York, Stimson recorded in his diary he was very concerned about “Morgenthau’s very bitter atmosphere of personal resentment against the entire German people without regard to individual guilt and I am very much afraid that it will result in our taking mass vengeance.” He added that such a clumsy economic policy would produce a “dangerous reaction and probably a new war.”35

Morgenthau retreated to Fishkill Farm but pressed his staff by phone to take an ever tougher line in their memo. “I wish that your men would attack the problem from this angle, that they take the Ruhr and completely put it out of business,” he said in a phone conversation with White and Pehle on August 31. “That’s one thing—and also the Saar.” He wanted them to research coal production and industry in the Ruhr and Saar—Germany’s industrial hub—and consider how Britain might benefit from the elimination of competition from these regions.

“This Ruhr thing is the most difficult problem,” said White. He was obviously uncomfortable with Morgenthau’s demands, even though he had weeks earlier initiated his boss’s interest in the German issue. “Crushing it, as you say, presents us with about fifteen million out of eighteen million people who—who will have absolutely nothing to do, and it’s trying to…” Uncharacteristically stumbling on his words, he explained the Ruhr was too big to give to another country, leave with Germany, or guard under an international mandate. “It's—it’s the most difficult problem, and we'll—we'll work along the lines you're suggesting.”

Morgenthau had no patience with White’s squeamishness, saying again that the Ruhr would be shut down. “I can tell you this,” he said. “That if the Ruhr was put out of business, the coal mines and the steel mills of England would flourish for many years.”36

Morgenthau had always respected his staff and worked with them to formulate policy, but now he alone was dictating the Treasury position, which he believed the president supported. On September 2, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt drove out to Fishkill Farm for tea, where they ended up discussing the German situation for a full hour. Morgenthau showed FDR a draft outline of the Treasury proposal. When they studied a map showing the proposed postwar partition of Germany, Roosevelt wasn't sure it represented the boundaries agreed to at Tehran. After some reflection, the president said the memo should include three paramount stipulations: first, that Germany should be allowed no aircraft of any kind; second, that no German be allowed to wear a uniform; and third, that no Germans be allowed to march in a parade. That, he said, would teach the Germans they were a defeated people.

“That’s very interesting,” said Morgenthau, who could only have been aghast that the aging president’s reaction to German brutality was to outlaw uniforms and parades. “But I don't think it goes far enough.” He urged the Ruhr be shut down as an industrial area. Making it an international zone would mean only that the Germans could seize it once again the next time they rearmed, he said. He agreed eighteen million to twenty million people may be put out of work, but they could be sent to other parts of the world, Central Africa, for example. The president supported Morgenthau’s proposal, as did Eleanor.37

Morgenthau was getting close to the proposal he wanted and assembled his staff one final time to refine the wording and add in stipulations on aircraft, uniforms, and parades. Again, White protested the loss of fifteen million jobs and suggested the Ruhr be placed under international control.

“Harry, you can't sell it to me at all,” rebuked Morgenthau. “T

he only thing you can sell me, or I will have any part of, is the complete shutdown of the Ruhr.” He wanted mines flooded and army engineers to blow up every steel mill, synthetic gas business, and chemical plant. “Just strip it. I don't care what happens to the population…. I am for destroying first and we will worry about the population second.” Herbert Gaston and adviser Robert McConnell also objected to the severity of the plan, but Morgenthau shot them down. “I am not going to budge an inch,” he said. “Why the hell should I worry about what happens to their people?” Gathering his fury he added: “We didn't ask for this war; we didn't put millions of people through gas chambers, we didn't do any of these things. They have asked for it.” He concluded by saying the president would go even further than he would. FDR was “crazy for something to work with,” he said, though it would be difficult to sell the plan to Churchill.38

On the evening of September 4, Morgenthau hosted a dinner with Stimson, McCloy, and White, at which he revealed his final plan for Germany. It was officially titled “Program to Prevent Germany from Starting World War III,” though it instantly became known as the Morgenthau Plan. Its dominant theme was the complete and immediate deindustrialization of Germany, but it delved into far greater detail. It wanted to dismember Germany, give Poland part of East Prussia and Southern Silesia, and give France the Saar and nearby territories. The Ruhr and its surrounding territories were to become an international zone. The remaining parts of Germany were to be divided into north and south sectors.

The German industrial heartland—the Ruhr, the Rhineland, the Kiel Canal, and the land north of the canal—would be stripped of all industry and mines so they could never be used by the Germans again. The plan did not demand reparations, other than the transfer of industrial equipment to the victorious powers.

Schools and universities were to be shut down until an Allied commission on education could write a new curriculum. All news media were to be discontinued until adequate controls on information could be imposed. All national-government officials were to be dismissed, and the occupying forces would deal only with local governments. The occupying military government was not to worry about such economic matters as price controls, rationing, or unemployment. For at least twenty years after surrender, the United Nations was to maintain controls over foreign trade and capital imports, with the aim of ensuring there would be no new industrialization. It banned—as Roosevelt had asked—German-owned aircraft, uniforms, and parades. It requested that continental armies police Germany, allowing American troops to return home soon.39

Stimson was polite, but his rebuttal was firm and immediate. He said Morgenthau’s proposal would mean the starvation of thirty million people. Morgenthau was surprised by the number, which was roughly double the figure of fifteen million people White had used earlier in the day. Stimson explained it was the difference between the population now supported by the industrial economy and the last time Germany relied on agriculture for its sustenance. He did not disagree with dividing territory or punishing war criminals, but he maintained that the deindustrialization of Germany would not prevent future wars.40

The venerable War secretary was even more emphatic the next day, when the cabinet committee chaired by Hopkins met. “More and more Stimson came out very emphatically, very, very, positively, that he didn't want any production stopped,” Morgenthau told his staff. “He said it was an unnatural thing to do, it ran in the face of the economy.” Stimson also used a term that he would use a few times in discussing postwar Germany. He said the Allies needed a policy of “kindness and Christianity.” Morgenthau apparently didn't say anything, but the implications and insensitivity of the word Christianity were not lost on him as Stimson mentioned it a few times.41

Though Stimson was immovable, Morgenthau held sway. Hopkins and Hull favored a tough policy. Stimson even wrote in his diary that Hull was “as bitter as Morgenthau.”42 Hopkins told Morgenthau that Stimson—the only participant who had not worked on the New Deal—didn't want to shut down German plants because “it hurts [him] so much to think of the non-use of property…. He’s grown up in that school so long that property, God, becomes so sacred.”43

The cabinet members brought their case before the president on September 6. FDR started off by saying they didn't need to make a decision in the first six months of occupation. Then he digressed to talk of how people lived in Dutchess County in 1810, in homespun wool, and there was no reason that Germans couldn't live that way. “He expounded on that at great length,” wrote Morgenthau. The meeting lasted only half an hour, and Morgenthau believed Stimson won the session.44

In the next few days, the War Department brought Morgenthau into the discussion on altering the handbook. The officials discussing the matter included Major John Boettiger, FDR’s son-in-law who had been living with his wife, Anna, at the White House and was working for the Civil Affairs Section of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. A journalist by trade, Boettiger had once written that FDR had appointed Morgenthau Treasury secretary because he knew Morgenthau would always do the president’s bidding. But he and his wife frequently wrote Morgenthau over the years to ask for favors, from advice on preparing their income tax in 1936, to Secret Service protection for their children in 1937. They later complained that the Secret Service had gone “somewhat haywire” and were considering protecting the family with tear gas and shotguns.45 Yet Anna Boettiger did not like Morgenthau and privately complained that he used her mother to fight his battles. There was speculation within Washington that she was planning a sort of latter-day regency, in which she and her husband would have key positions in aiding the president, who was too feeble to bear the burden of office alone.46

White and Bell were encouraging Morgenthau to be more assertive about the occupation marks, but Morgenthau brushed them aside, saying he had bigger fish to fry. He did however negotiate throughout the first week of September with Robert Brand of the British Treasury on the exchange rate. After several days, Morgenthau and Brand agreed to the level of ten marks to the dollar. Before the deal was signed, Brand needled the secretary to make sure the president was fully briefed on the discussions and had agreed on the ten-mark level. Morgenthau was utterly incensed by the man’s impudence. “A couple more like that,” he told White after Brand had left the office, “and he is going to be hoisted out of the window. I am not going to take much more of his—if you don't mind—God damned lip.” White dismissed Brand as a fool.47

But the truth was that Morgenthau had given Roosevelt scant details about the talks and didn't inform him fully that the British wanted a 12.5-cent exchange rate. “Now I told the President at Cabinet about the ten-cent mark,” he told his staff, referring to the meeting after he had met with Brand. “Just for the record, because I forgot, when I took it up with the President, I didn't tell him about the twelve and a half cent, because I remember his saying, ‘I don't like the twelve and a half-cent mark. I want a ten-cent mark.’”48 Morgenthau was for the first time acting beyond the authority of the president. Just a few years earlier, he would never have concluded an agreement with a foreign government without the full approval of Roosevelt.

Morgenthau also had a hand in writing the proclamation Eisenhower would read on entering Germany. He wanted the supreme commander to say: “We come as militant victors to insure [sic] that Germany shall never again drench the world with blood. The German people must never again become the carriers of death, horror and wanton destruction of civilization.” When he read it to McCloy, the under secretary of war said he wasn't too sure about the “drench the world with blood” part. Morgenthau assured him the president would love it. It was yet another indication that Morgenthau’s judgment was failing him. No doubt, he was suffering from hubris after the roaring success of Bretton Woods. He was now ignoring the advice of his staff and subtly manipulating the president. He was abandoning his successful formula as an administrator—develop policy with a great staff, sell it to a superior, and implement it.49

The three secre

taries finally submitted their respective proposals to the president on September 9 at a wrap-up session before Roosevelt left to meet Churchill in Quebec City. Roosevelt had privately assured Morgenthau not to worry, though the German plants might have to be closed gradually.50 FDR kept checking the Treasury’s document to make sure it included rules against uniforms and parades. When the president asked what would happen if the Soviets wanted reparations while the British and Americans didn't, Morgenthau responded that he had found the Russians to be “intelligent and reasonable” and would likely forsake reparations as long as there was something else in return. The meeting reached no conclusions. Hull, who seemed to be siding more with Stimson now, declined Roosevelt’s invitation to come to Quebec, insisting he was too exhausted. Since the Quebec Conference would deal with the British fiscal position, Roosevelt told the meeting he might invite Morgenthau.51

Morgenthau was nevertheless surprised when Roosevelt sent word on September 12 that he should be in Quebec City two days later. He and White quickly flew up to the ancient French Canadian city perched on a rocky outcrop overlooking the St. Lawrence River. It was the second time in thirteen months that Churchill and Roosevelt had met there. On August 1, 1943, the Chateau Frontenac, the Canadian Pacific hotel dominating the skyline, suddenly canceled three thousand reservations and posted armed guards. It sparked rumors that the edifice was either to become a military hospital or that Pope Pius XII was fleeing Italy and would set up a headquarters in the Chateau Frontenac. It turned out just to be a meeting of the great democratic leaders. Now they were returning, accompanied by their wives and advisers—even Roosevelt’s dog Fala—in September 1944.52

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler