- Home

- Peter Moreira

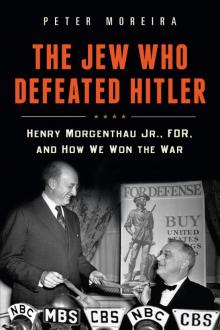

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler Page 8

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler Read online

Page 8

Blessed with attractively rounded features, blue eyes, and an affable manner, the North Carolina native worked in the family tobacco business before entering C. D. Barney and Company on Wall Street in 1920. Seventeen years later, following the death of his wife, he chose to help the country by joining government, first with the Securities and Exchange Commission, then the Treasury. He and Morgenthau soon formed a tight bond, and Hanes was one of the few Treasury men to call him “Henry” rather than “Mr. Morgenthau” or “Mr. Secretary.” Elinor worked to get Johnny Hanes III into Deerfield Academy, where the Morgenthau boys had studied. Henry Morgenthau Jr. at one point wrote his father to ask for advice on a property deal Hanes was considering in Purchase, New York.22 Hanes supported the administration, but never wavered in his belief in private enterprise as the solution to the nation’s ills. In private, he would say that it took an investment of $7,000 of invested capital to put one man to work, and from 1924 to 1929, private industry invested $450 million per month—a total injection of $5 billion per year into the economy. “What have we done since 1929?” he once asked some congressmen. “We have supplied less than $50 million a month. The result is a lag in our investment of over $3.5 billion a year.” His mission in the administration was to lure private investment back into the economy.23 “Hanes, like Secretary Morgenthau, very emphatically is a budget-balancer,” said Joseph Alsop and Robert Kintner in their column The Capital Parade. “He is also a believer in the importance of business confidence.”24

Hanes liked the column and even mentioned it to Morgenthau, drawing a sharp—and customarily wordy—rebuke from the secretary, warning of what can happen when influential journalists dub someone pro-business: “I want you to know that [New York Times Washington bureau chief] Arthur Krock hates the President and he and his group will do everything they possibly can to build you up in order to show that you are the man that has the businessman’s point of view, and they will reach the point where they will have you on the one side and the President on the other—you, saying ‘this is what business wants; this is what the country wants, and Hanes is the fellow to put it through,’ but with the President on the other side directly opposing you.” Morgenthau warned his young charge that he had to watch his step and not let himself be held up as the champion of business standing up to the president. “When the President’s machine goes to work on a fellow, God help him!” said Morgenthau.25

Morgenthau and Hanes formulated a plan to simplify the tax system, especially for business. Hanes long wrestled with the problem of whether the government needed to lower taxes (and thereby boost business investment) or raise them (to lower the deficit). In the end they came up with a plan to roll back the surtax on wealthy individuals to 60 percent from 90 percent. It would still be higher than the 25 percent level of the Hoover administration. They also wanted to lower corporate taxes to a range of 17 to 22 percent.26 They still had to convince the president that this was the best course of action.

“Mr. President, you may be surprised,” said Morgenthau at one of their regular Monday lunches in March. “I am going to tell you I want to see a boom in the stock market.”

“That’s all right,” replied Roosevelt.

“Because rising prices in stocks does influence the executives of business and we have just got to get a boom,” added the secretary. He later told his diary that, to his surprise, the president agreed with him.27

One day, Morgenthau was asked a question about some policy at a press conference and responded with his own question: “Does it contribute to recovery?” That, Hanes realized, was the key. He had cardboard posters printed up and distributed to all the senior offices within the Treasury. Soon all of Morgenthau’s inner circle had “Does It Contribute to Recovery?” placards on their desks. Morgenthau offered to give the president one, believing the president was a convert to their cause.28

Meanwhile, the Treasury took what action it could to make life difficult for the aggressors and to prepare the country for the coming conflict. The Treasury continued to pursue countervailing duties against goods from Germany, and the State Department continued to block these efforts, saying the resultant trade war would not only hinder American trade but also impact the Intergovernmental Committee on Political Refugees. The committee, which had been struck by thirty-two countries at a conference at the French resort of Évian-les-Bains, was hoping to secure German cooperation in pursuing a solution for the refugee problem. Never one to hope for enlightened cooperation from the Nazis, Morgenthau dissented, but Cordell Hull persuaded the president to postpone a decision on the tariffs. They were still waiting for the attorney general to rule on the legality of the United States imposing countervailing duties on Germany.29

On March 7, Morgenthau buttonholed Assistant Secretary of State Sumner Welles to press for tariffs on Germany. “I can see your position,” Welles told him. “It is obligatory for you to do it, but it puts this country in a terrible position.”30 The implication was crystal clear: Morgenthau was conducting policy as a Jew whereas Welles had the interest of the whole country at heart.

“I must carry out the law,” Morgenthau said, interrupting him. “I cannot, as a Jew, stop and think ‘is this good or bad for the Jews?’ I have told you this before.” He added he would resign before he would conduct policy in such a way.

Henry Morgenthau Jr. never wavered from his insistence that his opposition to the Third Reich sprang from his patriotism as an American and not from his reaction to Nazism as a Jew. In fact, he and his wife often worried about the public impression that he would create by identifying himself with Jewish issues or making statements against the Nazis. He'd once told his staff he would prefer to place duties on Japanese rather than German goods because he didn't want Hitler using him as the reason for the next act of German aggression. He imitated Hitler saying: “I have to fight because the American Bolsheviks, that Jewish Secretary of the Treasury, is trying to strangle me economically and I have got to fight that.”31 In the same vein, he apologized to Jewish groups when they asked him for help, saying he could not do anything for them that he would not do for other Americans.

Yet he pressured the attorney general to make a decision on the countervailing duties against Germany and then against Italy. He had White prepare a memo on how the United States could deprive the aggressors of badly needed war materials, especially petroleum.32 He questioned the legality of the Munitions Control Board allowing arms manufacturers to make shipments to Germany, arguing that it violated the Treaty of Versailles, which restricted Germany’s militarization. He was strident enough that Hull phoned the president to complain, and FDR let the Treasury secretary know his rival had called.33 In the end, Morgenthau succeeded only in having the government impose duties on Italian silk and other textiles, though even these tariffs were delayed.34

In China, the Japanese had captured most of the coastal areas, so the latest problem was how to actually ship what little material China could afford. Though goods were flown in from Hong Kong by an airline half-owned by the Chiang family, the main route was the mountainous Burma Road. Not only did the Japanese frequently bomb the route, it was also plagued by the corruption and incompetence of the only trucking company on the road, which was owned by Chiang’s brother-in-law, the influential multimillionaire T. V. Soong. American shipments were piling up at Haiphong in Vietnam because of the problems in shipping through Burma. Morgenthau suggested to K. P. Chen, the Chinese representative in Washington, that these problems could be overcome by forming an international transportation commission. It would comprise Chinese, French, British, and American representatives and a “very important American as general manager” to serve as “the dictator of transportation.” He explained that the Chinese buying process was superior to its transportation, and that had to change. “And there won't be this idea of Mr. Soong having a private transportation company,” said Morgenthau. “‘Out the window!’ as we say. He just can't have it. He can't be blocking the roads; can't have gasoli

ne; this is a government proposition. Trucks, railroads, everything is pooled.” Chen said he would forward the suggestion to Chungking.35

Of course, the aggressors continued their expansion. On March 13, Germany seized the remaining Czech portion of Czechoslovakia. Slovakia became a Nazi puppet state. It exposed the Munich Agreement to be the sham that Roosevelt and Morgenthau always knew it to be. In Britain, Chamberlain was chastened, knowing the next act of German aggression would bring about a pan-European war. Morgenthau looked into freezing all the Czechoslovakian money on deposit in the United States, and Roosevelt urged him on. It amounted to $3 million. The government didn't pursue it wholeheartedly.36

The US rearmament program and French purchases proceeded. Morgenthau asked Roosevelt’s permission to bring in four business executives to serve as dollar-a-year advisers to the Treasury. The president questioned one candidate, financier Earle Bailie, whom Morgenthau had tried unsuccessfully to appoint as assistant secretary in 1934. And FDR opposed the suggestion of Edward Stettinius Jr., the chairman of US Steel, worried that he would let the copper price rise as soon as war broke out. He suggested a few alternatives, including Leon Henderson, a left-wing economist. “I think the President is wrong and hope to convince him,” Morgenthau later told his diary.

What Roosevelt did want was Morgenthau to act on a suggestion from Joseph Kennedy that the Treasury, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Reserve, and other agencies ensure the New York Stock Exchange be prepared for the extreme volatility that would occur once war broke out. Morgenthau assembled a meeting on April 12 with Federal Reserve Chairman Marriner Eccles, Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace, and other officials, including Herbert Feis, the levelheaded economic adviser from the State Department. Feis, the Harvard-trained author of several books, often had the undesirable task of being the go-between for Hull and Morgenthau. They discussed how war would affect not only the stock exchange but also other markets, like commodities and foreign exchange, and late in the afternoon FDR called and gave them a 5:00 p.m. deadline to give him recommendations. As they reviewed their options, Feis interrupted and said he should report to Secretary Hull. Then he asked for his next comments to be erased from the record and yelled at everyone that they were pushing him around and acting like Fascists. While the others sat in stunned silence, Morgenthau said they were carrying out a job requested by the president, but Feis insisted they were dealing with things of which they had no idea.37

“I'm sorry to have been so semi-dramatic,” said Feis. Babbling on, he concluded: “But I'll tell Mr. Hull.”

“Think you can find your way?” asked Harry Dexter White.

“I find my way in a world that looks slightly different to me from the one that I entered.” He stormed from the room.

“That gave us the relief that we needed,” said Morgenthau. “Anybody want a drink?”

As the others laughed heartily, Morgenthau opened a bottle of sherry. They reached the deadline, agreeing that they should keep the markets open if possible and not invoke exchange controls unless absolutely necessary. Morgenthau briefed the president at the White House, including the tale of Feis’s strange behavior. When the group reassembled at his office at 5:40 p.m., Morgenthau called Hull to brief him and then called Feis to invite him to join them all for a drink.

When Feis entered, it was well past six o'clock. “Having a little drinkie?” asked Morgenthau.

“Just a little one,” answered Feis.

Handing him a sherry, Morgenthau told him they were only making plans, not commitments. Proposing a toast, he said: “Well, here’s to peace anyway, in the war, in the world and between State and Treasury.”

At the white-tie Gridiron Dinner that spring, one after-dinner skit featured a reporter dressed in a dragon suit, slumped, exhausted, and bandaged, with a few arrows sticking out of his rump. An announcer’s voice boomed through the darkened dining room: “The Gridiron Club presents King Arthur and his knights and wizards of the Round Table, who are confronting a grave emergency. Their pet dragon, named Business, after providing them with six years of rare sport, is about to expire.”

On to the stage walked two knights, morosely studying the wounded dragon.

“Sir Henry Le Morgue, I fear we have beaten this old dragon, Business, until he’s all in,” said the first knight. “It looks like he is going to die on us.”

“Yes Sir John of Hanes,” replied the journalist playing Morgenthau. “That’s what I've been telling King Arthur. But it doesn't seem to bother him a bit. He just smiles.”

“He’s spent six years trying to kill that dragon. Just between ourselves, even the common people are getting fed up with this abuse of poor old Business.”

“See! All he needs to make him healthy is—appeasement! Even if he is a vicious beast, and not to be trusted, we'll certainly need him in 1940. If he dies, we won't have anything to save the common people from.”

“King Arthur listens to those crackpot wizards—Eccles the Echo, Tommy the Cork and Benny the Cone. And how they hate the old dragon!”

Morgenthau loved the skit and secured a transcript that he filed into the Morgenthau Diaries. It was humorous relief from what was becoming a serious and very public disagreement between himself and his president.

Roosevelt had hated the Morgenthau-Hanes plan when they'd outlined it to him in March, calling it a “Mellon plan of taxation,” a reference to the conservative Treasury secretary of the previous administration, Andrew Mellon. The president didn't like lowering taxes for the wealthy and didn't trust the business community to generate jobs. “I think that sign on your desk, ‘Does it contribute to recovery?’ is very stupid,” he said flatly to Morgenthau at one White House meeting.38

As the seasons changed in Washington, Roosevelt was learning to detest two words that were becoming commonplace—appeasement and recovery. Appeasement had taken on unseemly connotations since the agreement in Munich and now often referred to the administration’s overtures to business. The New York Times reported the president didn't like the word and was looking for a substitute.39 The left wing of the Democratic Party, including FDR, also disliked the term recovery—and the blue cards that bore the word—because they thought it meant abandoning relief programs to encourage business expansion. “The blue card was immediately denounced to the President by the die-hards,” wrote the New York Times columnist Arthur Krock. “They said it was an open flag of surrender to the ‘reactionaries’ and to the bitterest partisan critics of Mr. Roosevelt’s Administration.”40

Morgenthau and Hanes were soon isolated into one faction that wanted tax revision to encourage private investment. Another group, led by Federal Reserve chairman Marriner Eccles, Tommy Corcoran, and Benjamin Cohen, opposed any changes to the tax system. Roosevelt leaned toward the Eccles camp, but Morgenthau refused to buckle under. In fact, he asked the president for permission to address a congressional committee to put forward the case for tax reform and prepared the remarks. In mid-April, Roosevelt and Morgenthau were getting along splendidly because the president was focused on a public warning he delivered to Hitler and Mussolini to halt their aggression. (Hitler dismissed the warning with a defiant speech in the Reichstag.) But as they focused more on the domestic economic problems, tensions mounted between 1500 and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

At their lunch on April 25, Morgenthau asked the president when he would like to see the tax-revision speech. About June 15, the president replied and let out a hearty laugh. It was the date the king and queen of Great Britain were due to end their visit to the United States. “Well,” said the president, “you spoiled everything. We had everything in nice shape for a month and now you keep saying the Treasury has a program.” Morgenthau countered that he'd said only that he was ready to make a statement if requested. He wanted to discuss the statement, but FDR jokingly said he was busy with royalty until June 15. Finally they agreed Morgenthau could give him a draft statement to look at.

As Morgenthau, Hanes, and

the Treasury intelligentsia drafted and redrafted the statement, the division within the Roosevelt circle became more public. Within Congress, Democratic senator Pat Harrison of Mississippi led the movement to add tax-revision clauses to a routine tax-extension bill that had to be passed by the end of the fiscal year. Roosevelt said the one had nothing to do with the other, and he was being assailed in the press for not showing leadership and restricting the Treasury from doing so. “What is needed and what is possible is not a series of little measures accompanied by verbal assurances, but an action, as decisive as his embargo on gold in the spring of 1933, which will cause the resumption of private investment,” wrote columnist Walter Lippmann in a column Morgenthau showed to the president. “The only thing which will bring that about quickly is to offer investors and speculators the inducement of profits large enough to overcome their inertia and their fears.”41

Morgenthau, meanwhile, received some of the best media attention of his career. In a column noting the secretary’s “courage and character,” Frank R. Kent of the Wall Street Journal noted Morgenthau had never received great press, so it was only fair to give him credit now. “Instead of curling up and saying, ‘yes, yes Mr. President,’ Mr. Morgenthau is sticking to his guns,” wrote Kent.42 Morgenthau, Hanes, and the longtime Treasury public-relations man Herbert Gaston pulled out every stop to win these plaudits. The New York Times’s Sunday magazine ran a glowing profile of Hanes on April 9.43 Shortly afterward, Hanes (who was also lobbying Republicans and moderate Democrats on Capitol Hill) traveled to New York to persuade the New York Times’s editorial staff to profile Morgenthau himself. On May 5, Krock phoned Morgenthau to tell him the results of Hanes’s trip were “100 percent successful.”44 A pleasing portrait of Morgenthau appeared in the Sunday magazine of America’s most influential paper on June 4. It noted that Morgenthau, in five and a half years, had matured from “inexperience and overcaution to practical mastery of perhaps the most important single administrative position of any government in the world.”45

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler

The Jew Who Defeated Hitler